GraphQL

Recently, I’ve been learning about GraphQL. For those who don’t know, GraphQL is a query language for APIs. It essentially allows a frontend to query a backend service as if it were querying a database. This is nice because it lets your frontend request only the data that it needs for each individual page.

For example, if we were making a blog platform, our frontend would need a page to display a list of posts, each of which has an author. A GraphQL query for the latest 100 posts might look something this:

query {

posts(orderBy: "createdAt", limit: 100) {

id

createdAt

title

content

author {

id

name

}

}

}

On the backend, this would be implemented through the use of resolver functions. In Javascript:

async posts(orderBy, limit) {

return await db.getPosts(orderBy, limit)

}

async author(post) {

return await db.getAuthor(post.authorId)

}

You may notice that for a list of 100 posts, this would trigger 101 SQL queries- 1 for the list of posts, then 1 for each author on each post. This is known as the N+1 problem because we have N + 1 queries (where N is the number of posts)- it typically comes up when talking about ORMs, but it’s the same problem here.

The N+1 Problem

I really liked the idea of GraphQL as it seemed to solve a lot of the problems I have traditionally had when writing APIs, but I never dug very deep into it because it seemed so inefficient.

For me, the “aha” moment was reading about dataloader. This is a pattern/software package/idea which lets you write code in a similar style to the code above, but behind the scenes, it batches up all of your author queries. All you need to do is tell it how to load a list of authors given a list of author ids. This would look something like:

authorDataloader = new Dataloader(keys => db.getAuthorWhereIdIn(keys))

async author(post) {

return await authorDataloader.load(post.authorId)

}

Cool! Now we get the same functionality as above with only 2 SQL queries. But we are still doing 2 database queries for what could have been done with 1 that uses a SQL JOIN. Could we have just done a JOIN with authors in our “posts” resolver? Sure, but then we are doing a JOIN for any posts query when the querier may not always care about authors. We could also try to get clever and inspect the GraphQL query to see if the querier does want authors and only JOIN with authors if they do, but that’s more code and is starting to muck up our resolver.

So there are some benefits to doing it this way, but what is the performance cost?

SQL Joins vs In-app Joins

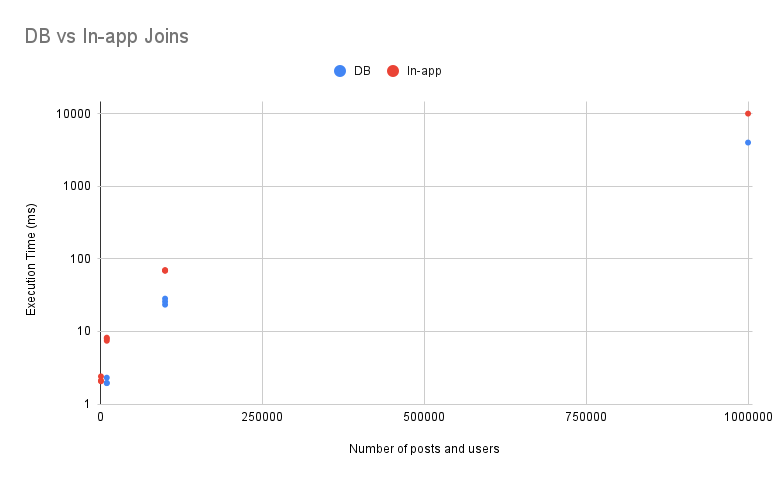

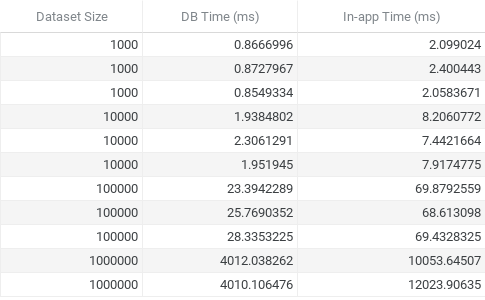

What this really comes down to is: SQL Joins vs In-app Joins. I’m curious to see what the performance difference is between doing a join in SQL vs implementing this join in application code, which is what the dataloader pattern is doing behind the scenes. I suspect that the SQL join will be slightly more efficient, but I expect the difference will be small enough that it won’t matter for most use cases.

Experiment Setup

To test this, I made a script which builds a PostgreSQL database on my laptop with posts and users, runs each type of query (db vs in-app) against the local database and times it. Each post has an author.

To test the SQL Join, the query I am testing selects every post and joins it with its author:

SELECT post.id, user.name FROM post LEFT JOIN user ON user.id = post.authorId;

To implement this in application code, first, I select every post and its authorId like so:

SELECT post.id, post.authorId FROM post;

Then, in my code, I gathered each authorId in a list, then issued a “WHERE IN” query to the DB like so:

SELECT user.id, user.name FROM user WHERE user.id IN (<authorIds>);

That gave me a list of (user.id, user.name) tuples, from which I created a hash map of id -> name. Then, I iterated through each post and joined it with its author in my hash map.

You can find the full code I used here: https://github.com/NickCellino/in-app-vs-db-joins.

So how did each perform?

(Note: “Dataset size” refers to the number of posts and users I created. In other words, dataset size = 1000 means I created 1000 posts and 1000 users)

As expected, letting the database perform the joins was more efficient. Doing the join in-app was slower by a factor of about 2.5. This will likely only be painful as you get into >100,000 row territory, as you can see. Ideally, you can do some filtering on your data before that so you don’t need to join so many rows.

Wrapping up

Though these results were predictable, it’s still nice to have quantified this and now, I have some concrete data to reason from. For most use cases, I think the code-cleanliness and flexibility of in-app joins will outweigh the slight performance penalty, but there will be obvious exceptions and cases where every last bit of performance is important.

Personally, I really like GraphQL and think the dataloader pattern is extremely clever and useful. Trying to write code that minimizes the number of SQL queries is often at odds with writing code that is simple to reason about and change. Dataloader provides an API that makes it easy to write code that is reasonably efficient as well as extremely simple and readable.